Radical imagination as a tool for social justice

Black children are the best teachers of liberation

Hiya family! Welcome back to Black Joy Behind the Scenes 📽️, where every Sunday I’ll be giving y’all a glimpse beyond the journalism veil of my nationwide media brand Black Joy. My mission is to chronicle the different ways we as Black people continue the ancestral practice of cultivating liberatory joy in our lives. The success I have experienced over the past week has shown me just how much my work resonates with a lot of you!

I don’t have the proper words just yet to express my immense gratitude. This time last week, I sent a newsletter to about 30 subscribers. On Friday morning, I woke up to the news that I had reached my first goal of 100 subscribers. Now, on Sunday afternoon, I’m eight people shy of 200. To celebrate this occasion, I’ve started a chat so we can have fun together! Y’all be patient with me as I figure out the tempo of how I’m going to interact with all of you. I want our conversations to be authentic and organic. That takes time :).

Since the majority of you came from my note about the aesthetics of my homepage, I decided to write a story about the inspiration behind my designs. I’ve been playing around with Canva for a few years now to make social posts and graphics for my brand. While this won’t be a step-by-step Canva walkthrough, I did want to give y’all a cultural reason as to why I create what I create.

Growing up in Alabama, the stopping grounds of civil rights, African American history was taught to me through black and white photos and some watered down context from a textbook. While color photography was rare in the early-to-mid 20th century, presenting a grayscale version of history made my young mind think that those racist, traumatic moments happened long ago.

I didn't realize my proximity to Black history in both time and space until adulthood. In 2016, I accepted a night reporter job in Birmingham, Ala., where I experienced history in living color. I interviewed residents who housed the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., and other civil rights leaders during their visits to the city. I've sat in the sanctuary of 16th Street Baptist Church, where a racist bombing in 1963 claimed the lives of four girls and left another girl blind in one eye. I reported on protests that have marched the same streets where Black children were sprayed by firehoses and attacked by dogs.

These spaces are still platforms of playfulness and happiness. To this day, 16th Street church stands as a monument of joyful resilience. Many heritage festivals have taken place on marching grounds. Writing about these moments has filled me up with so much vitality for my people.

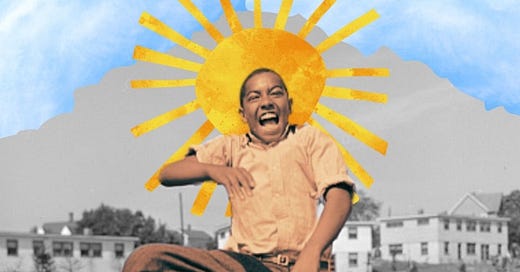

During a rainy Juneteenth, I decided to scroll around on the Library of Congress’ website where they have a selection of images that are free for public use. Their happiness collection intrigued me. So I downloaded a couple of images and decorated them with colorful, bright illustrations:

After working on these images, I have since thought about radical imagination as a tool of social justice. It gives us the power to reimagine a world constructed by Black joy instead of the absence of it. What we envision emboldens us to live more authentic lives no matter the oppression of white supremacy. I decided to post imagery that highlights that joy.

I'm going to explain one of those photos today. I may turn this into a series to talk about the rest of the images I did, depending on y’all’s interest! So let me know your thoughts in the comments!

When my sister told me she was having a son, I was filled with an enthusiasm singed by fear and frustration. The calamity of 2020 filled the duration of her pregnancy. White supremacy claimed the lives of Ahmaud Arbery and George Floyd. The legalized assault on our First Amendment right to protest erupted in the streets. Seeds of antiracism were sown into America’s consciousness, but they didn’t bloom into the nation’s being. Witnessing these moments all at once made me worry about the type of world my nephew would experience.

Here, Blackness isn’t perceived as extraordinary. We are marked as dangerous before we exit the womb. Generations worth of imagery and lore have spun lies about who we are as Black people before we even get to decide who we are. I can yap on and on about how these stereotypes endanger the well-being of Black women and queer people because those identities are the ones I relate to the most. But this is also true for Black men.

Black boys – children – kids – little ones lose the assumption of innocence as early as age 10, according to a 2014 American Psychological Association report. This bias often puts Black children in the crossfire of carceral violence. While I have seen many men overcome the stereotypes placed upon them, I’ve seen the same amount of men become drained, and even deranged, by the heaviness of whiteness.

As I stated in a previous post, James Baldwin also wrote about his nephew’s birth into a dark, racist society. But he didn’t just leave his teen family member in fear. Baldwin also spoke about the forcefield of Black love that was formed the day his nephew entered the world.

“I know how black it looks today for you. It looked black that day too. Yes, we were trembling. We have not stopped trembling yet, but if we had not loved each other, none of us would have survived, and now you must survive because we love you and for the sake of your children and your children's children.” ~ James Baldwin, “A Letter to My Nephew”

Baldwin points out how even when we tremble, love is still possible. My nephew was enveloped in love the moment he left the womb. Even when the world is collapsing, my nephew’s laughter fills the sky. His smile is one of the brightest things I know. He has an appetite for learning and expresses this by singing his numbers and colors. He’s still at that age where his sense of exploration knows no boundaries. This used to give me panic attacks, but now, with some safety parameters put in place, I admire his ability to say, without uttering a word, “I am here and I will always belong here.”

I hold a powerful lesson in my arms every time my nephew hugs me: Black love and joy are preventatives and antidotes in a world that wants to keep you ill with racial hatred.

That is what I wanted to convey in the above picture, which was captured by the iconic photographer Gordon Parks. It shows two Black boys laughing as they play leapfrog near the Fredrick Douglass projects in Washington, D.C. Now, I didn't grow up in the projects, but I know many people who did. It's where women would braid beauty into my hair while asking me how I am doing in school. It's where I chit chatted with my homegirls over Kool-Aid cups made by the neighborhood candy lady. A woman named Quanna Bolden, who grew up in the projects in Savannah Ga., created a whole nationwide movement called Carefree Black Girl because of the cookouts and talent shows she experienced as a child.

“I actually don’t regret being a project kid,” Bolden told me in June 2024. “That’s where I first learned the importance of community. It really was a village that exposed me to the arts and forged the foundation of my existence.”

I'm certain many of our celebrities and artists who came out of the hood would agree with Bolden. But despite this evidence of joy and creativity, I have seen many projects become infested with multiple misconceptions. I've reported on meetings where city officials have labeled these homes as eyesores riddled with poverty and violence, even though it was the city that failed to take care of its own property and people.

Parks, like me, saw the projects as a playground of Black magic. I wanted to bring out that essence when I created an image I titled “Black Sonshine.” The children featured in the photo exude a Black boy so powerful that it produces a world bursting with color. Blue skies start to encroach on the grey of their lives. And – just like my nephew – they carry the sun in their smiles.

Black children are wonderful educators. Through their very existence, they teach us the liberation of love and how to be free. I think that is what makes them “dangerous” in the eyes of white supremacy. Imagine all of us following the youth's footsteps and living in a way that said:

“I am here. I belong. And it is my Blackness that makes me free.”